I found this section of the exam pretty difficult. The thing I found most difficult was that in the exam they specifically ask you to draw a lifecycle diagram to help describe the lifecycle of a certain pest. Most of the diagrams do not appear in any of the textbooks, so I have created my own using information from the past papers (they publish the kind of answer they want, but don’t provide the full marking scheme, or any kind of example of the sort of pictures they want). If they don’t ask for the lifecycle of a particular pest, I haven’t given it here, just what they do that is damaging. I really hope you find this section helpful, as the question this is asked in usually carries a lot of marks.

One good thing about drawing my own diagrams is that nobody would think that I had cut and pasted them from their site. I hope they are good enough for you to get the idea though.

A pest is defined as anything which is damaging to plants. It can be an animal, bird, insect, mollusc etc.

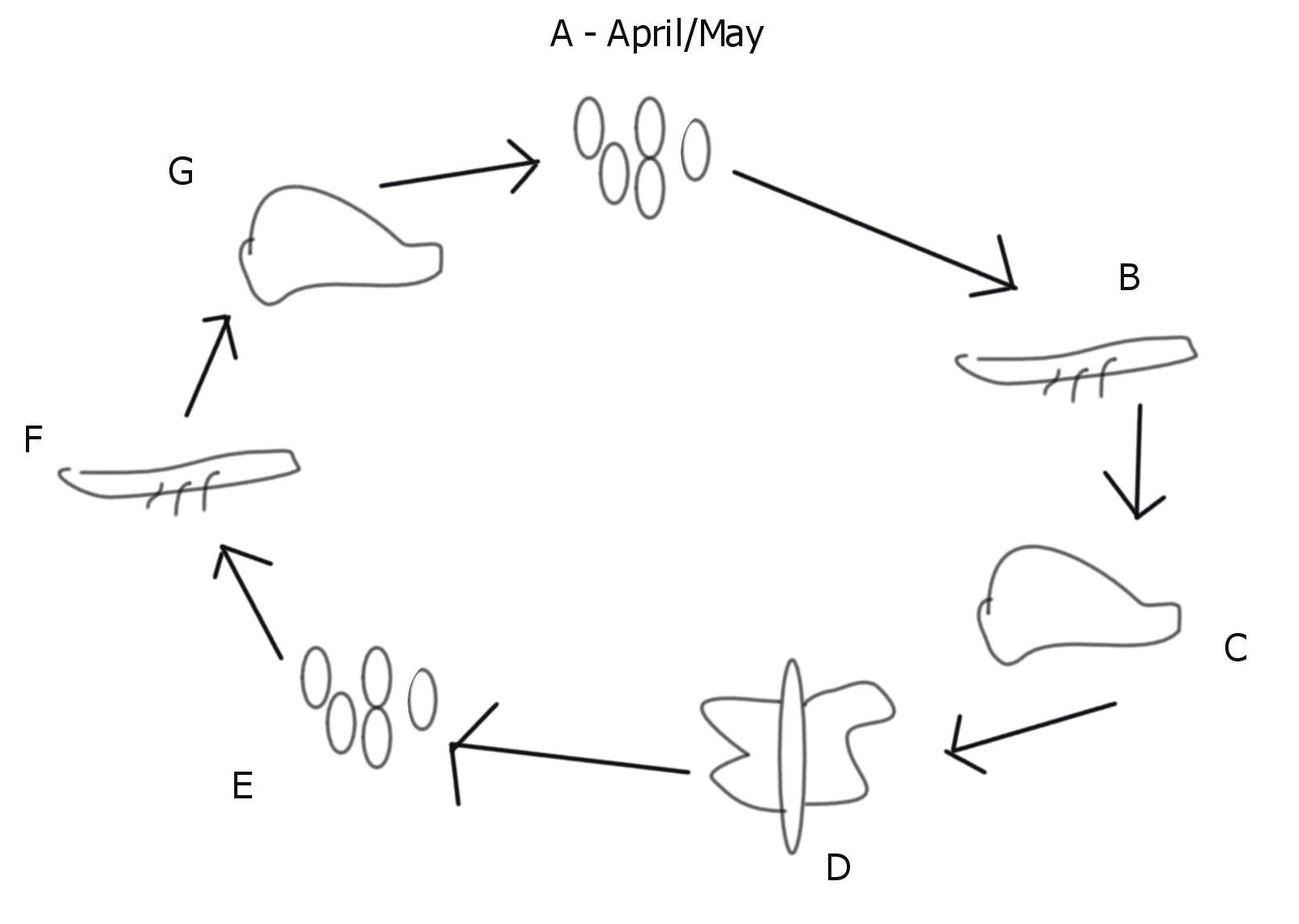

Cabbage white butterfly

It is the caterpillar stage that does the damage. Going around the diagram starting from point A:

- A – yellow, oval eggs are laid on suitable host leaves in April or May. There is a photo of that

- B – caterpillars hatch and feed on the leaves. They are blue/black with yellow stripes. They moult 4 times.

- C – the caterpillar forms a pupa to undergo its change. This happens around June/July. Apparently, the trigger to pupate is driven by weight, so caterpillars are very hungry!

- D – butterfly emerges from the pupa in July/August. They mate with each other.

- E – Eggs are subsequently laid

- F – the second generations of caterpillars this year emerges in August/September

- G – The caterpillars form pupas and survives over winter in this stage. They will emerge in the spring to start stage A again.

Cabbage whites can be controlled by covering brassicas with netting (since they are the caterpillar’s favourite food plant). There is also a biological control, a parasitic wasp called Cotesia glomerata.

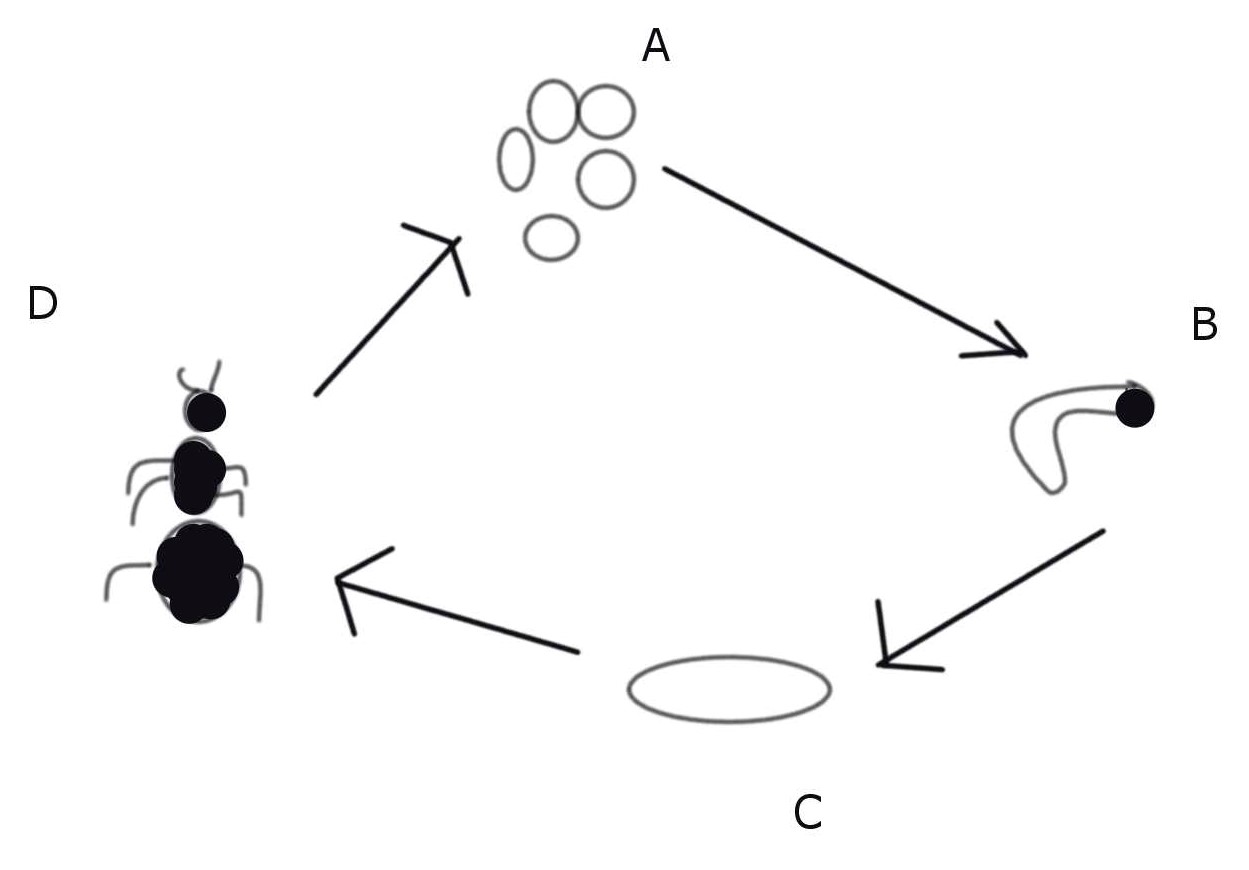

Black bean aphid

All aphids are basically the same. The suck the phloem (sugars) from plants and excrete the excess which leads to a mould covering the plant. Black bean aphids like beans and cause restricted growth and mis-shapen beans.

- A – The eggs have overwintered in the stems of a host Euonymus

- B – the eggs hatch in spring and un-winged females emerge.

- C – The females reproduce asexually. These clones are all female and do not have wings. The clones can all reproduce themselves as well within a matter of days. Winged forms develop due to overcrowding or seasonal changes so that they can fly off to find another plant to feed on. These then reproduce asexually again, more un-winged females.

- D – in the autumn, winged males are produced, as well as some winged females. These can fly off to find each other and mate. The eggs are laid in a host tree to start point A again.

Black bean aphids can be controlled by encouraging their natural predators in to the area, like ladybirds or hoverflies. You can spray on chemical pyrethins which block the spiracles (breathing holes) of the insect, causing suffocation. There is also a biological control in the form of a parasitic wasp, Aphidius colemani.

For more information, see: https://www.rhs.org.uk/biodiversity/aphids

Or: https://www.leafylearning.co.uk/post/black-bean-aphid-life-cycle-and-control

Peach potato aphid

No lifecycle needed for this one. It is just another type of aphid, feeding on the phloem of a plant. The waste excreted by the aphid can block the stomata of the plant and also cause fungi to grow, like sooty mould. You can try to control it as for the black bean aphid.

Two-spotted spider mite

Also called the red spider mite. No lifecycle needed for this one either. It bites into leaves and injects a poison which kills the cell. They then suck out the cell contents to feed. They are really small and difficult to see. They can be controlled using chemical fatty acids (they break down the cuticle of the insect and cause it to dry out and die), or a predatory mite called Phytoseiulus persimilis.

Glasshouse whitefly

This is only really a problem in greenhouses. It looks like a little white moth and is another one that sucks the phloem from your plants with the same mould problems. It particularly likes pelargoniums, fuschias, cucumbers.

- A – the small white, oval eggs are laid in a circular pattern on a leaf. One whitefly can lay about 100 eggs in its lifetime.

- B – The eggs hatch in to a crawler stage after 6 days

- C – the crawlers find a nice place to settle and insert their mouth parts in to a leaf an start to suck the sap. They become immobile scales.

- D – there are several scale stages (6 or 7). A parasitic wasp used for control (encarsia formosa) only works on the last 2 stages.

- E – the adult emerges from the nymph case of the last scale stage. These can be male or female. These mate and lay eggs to begin the cycle again.

Glasshouse whitefly is active all year round in a greenhouse. Control using a parasitic wasp, Encarsia formosa, or using fatty acids regularly. The scales have a really tough coating so several applications of fatty acids might be needed.

Vine weevil

I didn’t think to take a photo of the adult I found in my garden a couple of months ago. It was frankly bizarre – it didn’t seem able to walk very well and was a dull black colour.

The vine weevil is a type of beetle. The adult is not really the problem, the grubs are. All of them are female and they do not need to mate to reproduce. They are a particular problem with plants in containers.

- A – round, brown eggs are laid in August/September in the soil near a suitable host plant (begonia, primula etc). They are very small and very hard to see. About 1000 eggs will be laid in different places.

- B – the eggs hatch out grubs about 2 weeks later. The grubs are a white-ish colour, with a brown head. They are about 1 cm long and in the shape of a letter “C”. They eat the roots of the host plant.

- C – the grub pupates in the soil in late spring

- D – the adult appears in June/July and walks to find a good place to lay eggs. An adult can live for years

The vine weevil can be controlled using a parasitic nematode called Steinemena carpocapsae. Traps of corrugated card can also be left near infested plants to stop the adults.

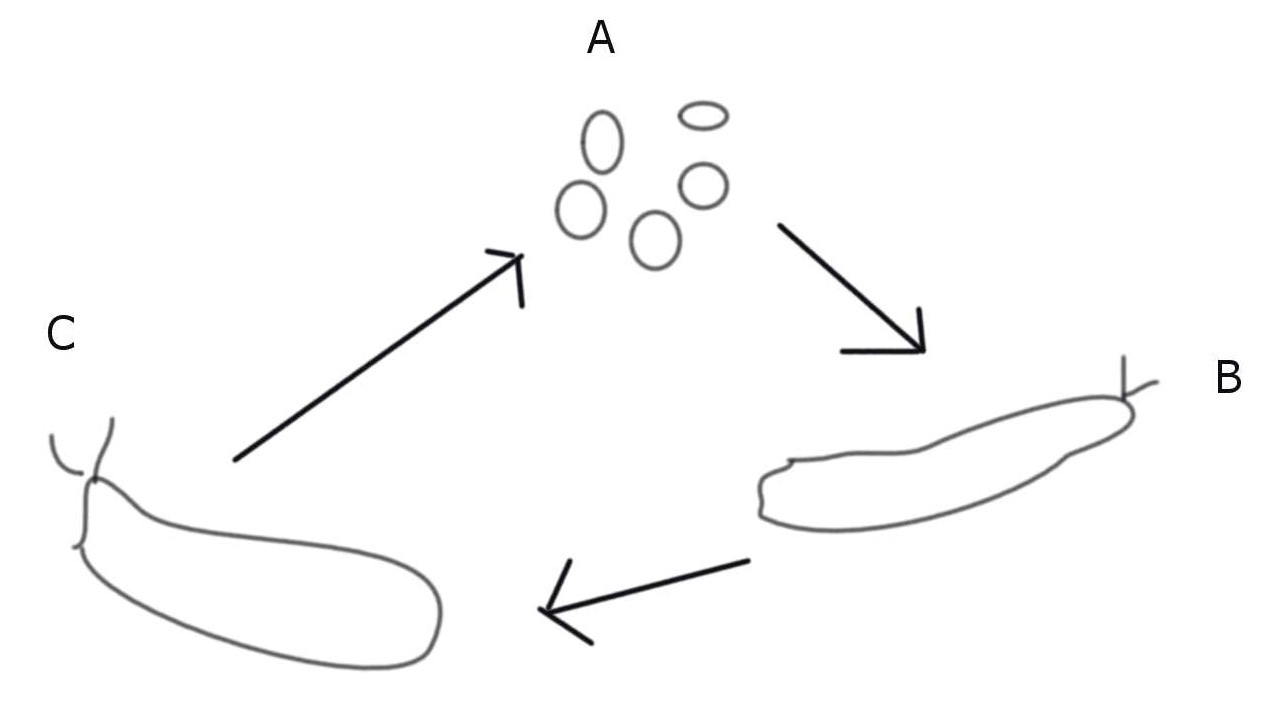

Slugs

Ugh, even the word makes me shiver.

Slugs are a pest because they eat lots of green growth. They have a rasping tongue (radula) which they use to cut through leafy growth.

- A – eggs are laid in batches of 10 -50 in moist soil. These are white and spherical. These eggs hatch in about 2 weeks. A slug can lay around 300 eggs in a lifetime.

- B – the eggs that hatch in the summer allow a juvenile slug to emerge. It will survive the winter as a juvenile. Some eggs will not hatch in the winter, but will hatch when the weather gets warmer.

- C – the slug feeds and gets bigger. Slugs are hermaphrodite, but they still need to mate with each other. Eggs are laid to start the cycle again.

Different species of slug have different lifecycles and lengths, but several generations of slug can be present at the same time. They can be controlled using a parasitic nematode, Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita or pellets such as metaldehyde. You could also choose slug resistant cultivars.

My own slug control attempt:https://rhslevel2studies.home.blog/2020/04/29/slug-pub/

Potato cyst eelworm

This is a type of nematode. It can survive inside the cyst (which looks like a small onion) in the ground for 10 years. If it attacks a potato, the leaves go yellow and the plant growth is stunted.

- A – the cyst is in ground which has previously been used to grow potatoes.

- B – The nematodes are stimulated by exudates from the root of the plant and make their way to the potato plant. The nematodes feed on the roots using a spear-like mouth which they use to suck out cell contents. Once mature, the male and female nematodes wriggle to the outside of the root to mate. The female leaves her head in the root though. The female’s body swells up and forms the cyst with the eggs developing inside her.

- C – the female’s body changes colour, becoming brown and falling from the root. The cyst has 200 – 600 eggs inside.

Crop rotation can help control potato cyst eelworm , although since it can survive in the soil for 10 years, it would need to be a really long rotation. A green manure can help because it can increase soil fungi that parasitise the nematode. Resistant cultivars are a good way to try to avoid this pest.

Rabbits

No lifecycle for this one. Rabbits eat plants and also strip the bark from trees. They can be controlled using fencing where the fence or netting is buried at least 30 cm underground. They an also be repelled by aluminium ammonium sulphate.

That was a long section – thanks for reading through it. Remember to like this if it was helpful to you!

Really useful lifecycle diagrams – thank you!

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Really useful thanks! TBH I think it’s pretty unfair that they ask for diagrams without actually providing the information….

LikeLike

Thanks for this blog. It’s really useful as, like you said, decent simplified lifecycle diagrams of the pests are hard to find. One thing I noticed was that in the Black Bean Aphid lifecycle my learning materials from Royal Botanical Garden Edinburgh and the examiner notes from past paper June 2019 R2103 both say that ‘wingless’ females emerge from the eggs, not ‘winged’! Many thanks again

LikeLike

Thanks Tim – this is exactly why I would like the RHS to publish something (a text book maybe) to show definitively what answer they want! I’ll edit the post to put that right, and direct people to the RHS website: https://www.rhs.org.uk/biodiversity/aphids and also Leafy Learning: https://www.leafylearning.co.uk/post/black-bean-aphid-life-cycle-and-control

LikeLiked by 1 person

A great resource. Thanks a lot for sharing!

LikeLike

You are my hero. I love your diagrams. Thankyou so much!

LikeLike